Controversy Bolsters International Popularity for Montenegrin Author Andrej Nikolaidis

Controversy in the arts is nothing new. Some of our greatest and most creative artists, authors and thinkers have regularly generated debate for their boundary-pushing work and forthright commentary on contemporary issues and the society in which we live. It could even be argued that, as a society, we need our great thinkers to open debate and provoke difficult discussion, even though their forthright comments and opinions might rile the populace and could be met with hostility.

Controversy in the arts is nothing new. Some of our greatest and most creative artists, authors and thinkers have regularly generated debate for their boundary-pushing work and forthright commentary on contemporary issues and the society in which we live. It could even be argued that, as a society, we need our great thinkers to open debate and provoke difficult discussion, even though their forthright comments and opinions might rile the populace and could be met with hostility.

In the Balkans, few other artists have raised the hackles of so many people as much as author Andrej Nikolaidis.

As well as a rising star of central European fiction, Andrej Nikolaidis is seen as a figure who is unafraid of controversy, frequently speaking his mind on deep-rooted issues that can inflame strong sentiment in the Balkan region.

Prominent Young Montenegrin Author

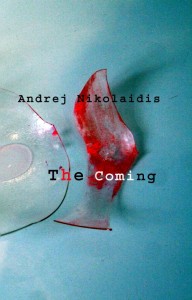

Andrej Nikolaidis, who was described by The Economist as one of Montenegro’s most prominent young writers, is probably best known internationally for his outspoken political opinions and high-profile legal troubles. But that should be about to change, thanks to the efforts of London publishing house Istros Books, which is making the works of Andrej Nikolaidis available to English-speakers. First to be released, in an excellent and faithful translation by Will Firth, is The Coming (Dolazak), to be followed in September by The Son (Sin), the winner of the 2011 European Prize for Literature.

Nikolaidis was born to a Montenegrin-Greek family in Sarajevo. His childhood was spent between Bosnia and Montenegro, finally leaving the besieged city in 1992, at the outbreak of hostilities. The subsequent collapse of Yugoslavia can be seen in much of his writing, and is behind the metaphor of the impending apocalypse that plays such an key role in The Coming.

Inflammatory Column in Monitor

The start of the strong feeling for Nikolaidis came in 2004 when he published what was seen as an inflammatory column in Montenegro’s Monitor magazine. In his article, titled The Executioner’s Apprentice, Nikolaidis, an anti-war activist and supporter of human rights, appeared to denounce Serbian film director Emir Kusturica for the content of his work during the Milošević years. The claims were strongly rejected by Kusturica, who sued for libel and, after a bizarre round of trial-and-appeal ping-pong, during which Nikolaidis was first ordered to pay €12,000 damages, before the higher Ustavni Sud court ruled that Nikolaidis did have the right to write the article. Too late, though, as the money had already been paid, with financial support from fellow artists and media in Montenegro and Bosnia.

Early in 2012, it kicked off again, as his satirical comments on an incident in Banja Luka whipped up a Balkan storm in a controversy that even cost the scalp of the head of Serbia’s National Library.

When an arms cache was discovered in a building where Serbian President Boris Tadic was due to appear alongside Republika Srpska’s leader Milorad Dodikto celebrate the 20th anniversary of the Bosnian-Serb entity, Nikolaidis wrote a sardonic online piece titled ‘What is Left of Greater Serbia’, where he denounced jingoism and social hypocrisy and accused Serbian officials of undue influence over Republika Srpska and questioned the founding status of the Bosnian Serb entity. Most inflammatory, some saw his words as saying that civilization could have been advanced if the explosives had been used. Unsurprisingly, this caused outrage in Serbia and politicians used furore to fuel their pre-election campaigns.

Support From Belgrade Writers

Many writers in Serbia stood up for Nikolaidis and his right to free speech. The Belgrade Writers Forum condemned the ‘witch hunt’ that had been stirred up by media in Republika Srpska and Serbia and encouraged people to make up their own mind by reading the article in full. An official protest was sent to the Montenegrin foreign ministry, while one Serbian newspaper described the comments as ‘Hate speech from Podgorica’ and journalists in Republika Srpska filed a criminal complaint against Nikolaidis. Unsurprisingly, the previously offended film director Kusturica called Nikolaidis ‘the Taliban from Podgorica’.

The tempest did not end there. When a Belgrade tabloid picked on Sretan Ugricić, the Director of the Serbian National Library, for expressing his support for the right to freedom of expression, Serbia’s Police Minister Ivica Dacić said that the Director should be imprisoned for allegedly supporting terrorism (even though no criminal charges were ever brought against him). The library’s director denied this, repeating his support for free speech, but was sacked by Dacić, against the recommendation of Serbia’s Culture Minister Predrag Marković and to the criticism of legal leaders in the country.

Back in Republika Srpska, Milorad Dodik was clearly ruffled by the incident. On hearing that Nikolaidis had been awarded a literary prize by the EU, he reacted with a characteristically coarse comment.

European Prize for Literature

Of course, the level of publicity generated by such a reaction did not harm the popularity of Nikolaidis as one of the Balkans’ foremost young commentators and authors. In some ways, it has directly promoted his works to a whole new audience. Since winning the European Prize for Literature 2011, his works have been will be published to great acclaim across Europe.

The Coming is Andrej’s first book to be published in an English translation. This book, which is set in the coastal town of Ulcinj, is many things: a crime noir thriller, historical mystery, exposé of life in a provincial town, and an (im)morality tale about the collapse of society in the face of the coming apocalypse. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, it is also a book that has drawn comparisons to Umberto Eco and Orhan Pamuk.

The Coming begins with the massacre of a young family, an arson attack on a library and a midsummer snowstorm. When local police are unable to solve the case, an old school private detective is brought in to investigate.

As the detective investigates the various crimes and misdeeds in the town, his son returns from a psychiatric facility in Austria, adding to his emotional turmoil and providing opportunity for Nikolaidis to explore the relationship between a father and son.

The Truth is Sacrificed

This theme echoes Andrej’s most recognised work, The Son (Sin), for which he won the EU Prize for Literature. The narrator in that book, to be released in an English translation by Will Firth (Istros Books), is a writer who cannot adapt to the changing times and struggles with an on-going conflict with his father, who blames him for his mother’s death. Again, that book is set in Ulcinj and plays heavily on the multicultural aspects of that town.

As well as dealing with the strained relationship with his son, the detective in The Coming makes a choice about how much truth he reveals to his clients. In the first half of the book, he is seen to keep his clients happy by giving them only the information they want to hear, even at the sacrifice of the truth, such as when jealous spouses are gladdened to hear that their suspicions are justified or when every death should have meaning.

Truth and our shifting perspective on it is clearly a focus for Nikolaidis. With the seemingly imminent apocalypse, the people in the story become more and more inclined to sharing their truths, while the main character continues to hide the truth from people for their own good. Nikolaidis seems to infer that we are most honest with ourselves when we are backed against a wall, when self-preservation is our aim. Like it or not, this is when we are most true to ourselves.

Apocalypse in Yugoslavia

On top of this, the apocalypse is looming on the horizon, used by Nikolaidis as a metaphor for the collapse of Yugoslavia. The end of the world seems to be causing the people of Ulcinj to forget previously accepted standards and morals. As Nikolaidis describes it, Ulcinj is a place of quirks and dark characters, where antisocial behaviour is rife and rich in its variety. But it is not just that the people and their acts are immoral, it is that their world seems to have lost its moral compass. When accepted boundaries are abandoned, there is nothing to keep thoughts and deeds in check, Nikolaidis implies, drawing inevitable parallels with the region’s recent history.

Later in the book, Nikolaidis recounts the life of Fra Dolcino, a heretic born in the late 13th century, who announced the return of the Messiah, and details the life of the heretical cabalist Sabbatai Zevi, who proclaimed himself the Messiah before dying in Ulcinj.

Poetic, Thought Provoking & Comic

Clearly, this is more than a standard detective novel. The writing style is poetic, thought-provoking and, at times, darkly comic, while the use of straight narrative, historical story telling and even a stream of emails between the father and son, ensure that each tier of the story maintains its personality within the novel as a whole. Thankfully, these literary styles and tricks are well executed and do not jar in any way, which is testament to the skill of Nikolaidis.

Like The Son, this book also comes with its own suggested soundtrack, a list of songs by artists such as REM, Nick Cave and The Smiths, hand-picked by Nikolaidis as an accompaniment to the book.

Nikolaidis is a writer of great vibrancy and visual poetry. His descriptive prose is a joy to read. It begs to be read at ease, to luxuriate in the language and the choice of words. While it took me longer than usual to finish, this was not because the story was dull or tedious, but because I savoured each page and did not want this thought-provoking book to end.

No comments yet.

Be first to leave your comment!